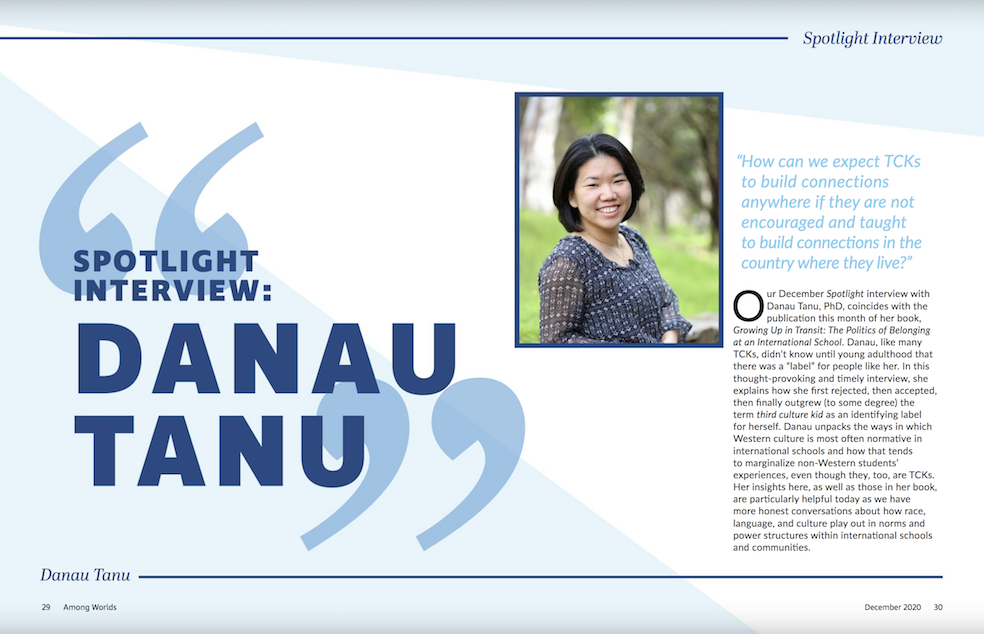

Danau Tanu

When there’s not a pandemic on, children spend an enormous chunk of their lives—at least seven hours a day, five days a week, 180 days a year—at school. It gives them plenty of time to internalize the social hierarchies that they experience at school. This includes social hierarchies that are informed by race—the kind of subtle racism that happens even when nobody intends for it to happen.

So, what happens when children internalize these racist structures?

Those structures become the stick by which children measure themselves, their peers, their parents, and their world.

Children learn these structures at a very young age through, among other things, the language they speak, the authority figures they see, and the curriculum they learn.

The power of English

“When I spoke English, I felt smart!” Lianne laughed as she looked back on her childish self when I interviewed her at her kitchen table in the condominium that she shared with her Indonesian husband.

Lianne is an international school alumna whose father is Singaporean and mother is Indonesian. Lianne didn’t learn English until she started attending kindergarten at an English-medium international school in Indonesia. Up until then, she spoke Indonesian at home. So, when she first started school, she was placed in an “ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages)” class.

It did not take long for Lianne to learn that English was a language of power. She soon learned to use English to challenge her mother’s authority.

“My mom spoke to me in Indonesian. My mom speaks great English but she prefers to speak in her native tongue. But, you know, the more I learned English, the more I was able to talk back to her in English. And it made me feel smart… so much more clever than my mom!”

Lianne remembers that she also picked up hand and facial gestures at school that she would deliberately use at home knowing that those mannerisms were foreign to her Indonesian mother.

Unbeknownst to Lianne at the time, her mother had continued to speak to her in Indonesian from a desire to pass on her heritage. “Later on I find out, when I’m eighteen or whatever, she didn’t want me to lose my native tongue.”

Standing on a pedestal

The sense of superiority that Lianne picked up at school spilled over into her views towards fellow Indonesians besides her mother. While she now no longer judges others for their accent or fluency in English, she admits she was not like that as a child.

“When I was a little kid, I would’ve been a complete snob about it because it means I’m much more superior.” Lianne explains that she learned these attitudes through the international school. “All of a sudden you’re on a pedestal. There was a feeling of superiority because of the affiliation, because of the command of language, because of people you hang out with, because of the extracurricular activities that were bountiful.”

As a child, Lianne says that she felt her international school “was much more advanced, if not interesting, than the local schools.”

White like Dad

Nick, a white American teacher at an international school, was also candid about the way his mixed-race daughter, Lara, internalized racism. “It’s weird because Lara is actually a little bit of a racist. She really kind of looks down on Indonesians,” said Nick.

According to Nick, Lara refuses to identify as Indonesian like her mother, and instead chooses to identify as white, like her father. “I made some sort of a deprecating joke about being the only bule [pronounced ‘boo-leh’, Indonesian slang for ‘white people’],” Nick recalled of a family dinner, “and Lara’s like, ‘No, I’m a bule.’” Nick said he tried to explain to his daughter that she is “mixed” but Lara rejected the label. “‘No, no, no, I’m bule’—that’s the way she sees herself,” Nick continued.

Nick taught at the same international school that his daughter attended. While he firmly believed in the multiculturalism that the school promoted, he didn’t feel the school was doing enough. “I just don’t want them to look down on their mother because they go to school in this environment,” he worried.

Nick believed that nobody at the school was intentionally teaching racism, but that it was being taught anyway because “there’s institutionalized racism.” He added, “I think it’s hard to escape that. I can see that that is part of the culture that my daughters are growing up in and that concerns me.”

Unlearning racism

As adults, many who have internalized the belief that their own kind are inferior may come to terms with their mistake and recognize the pain it had inflicted on others and themselves. They may learn to keep their racist attitudes in check by not acting on them.

But to unlearn and dismantle something that was implicitly absorbed and internalized over 12 or more years of daily exposure at school—and often reaffirmed outside of school—takes time.

Prevention is the better antidote.

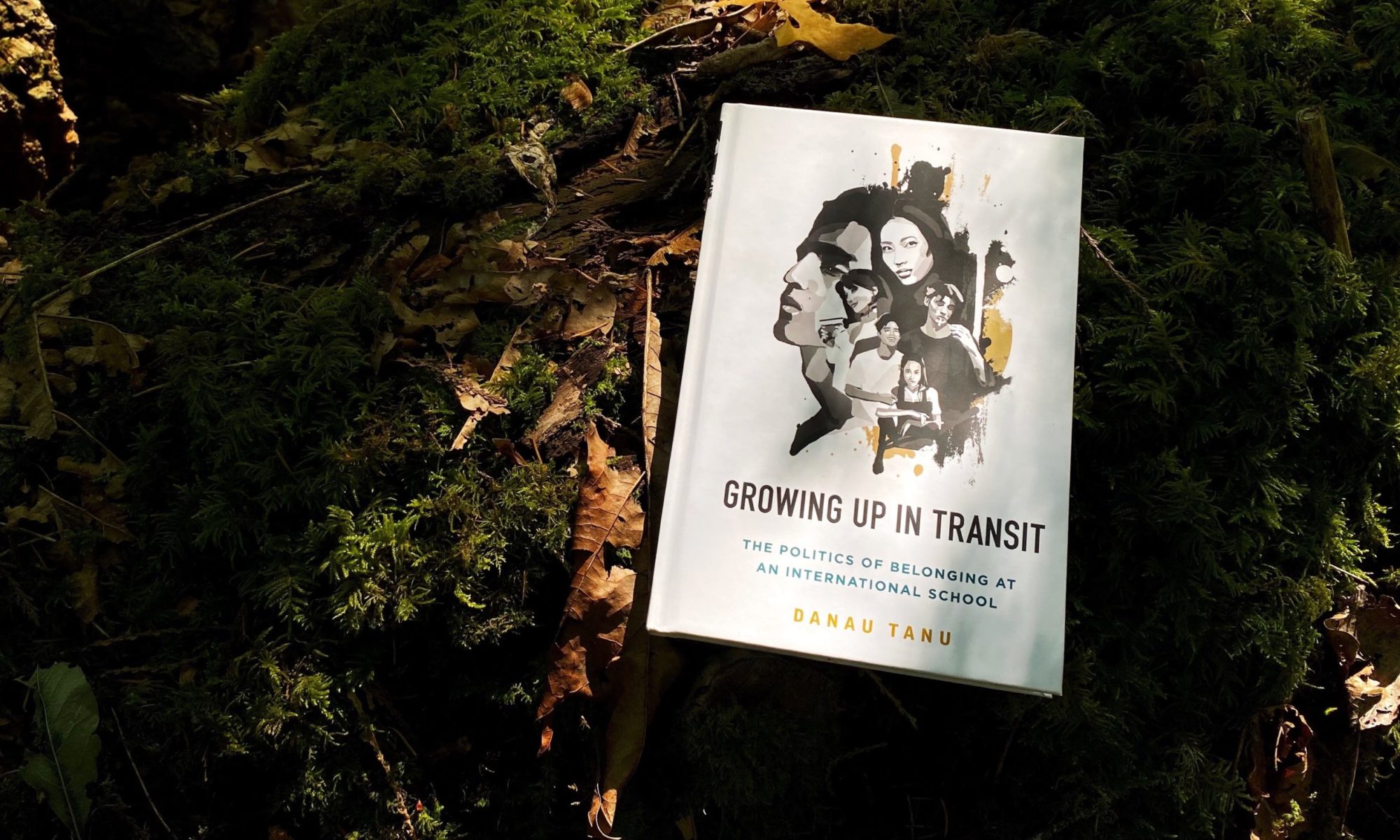

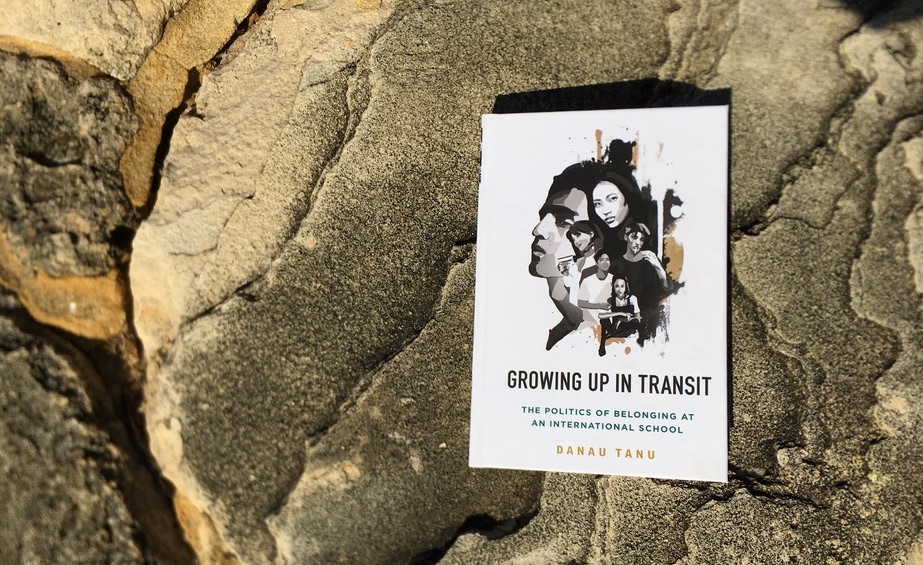

Danau Tanu, PhD, is an anthropologist and the author of Growing Up in Transit: The Politics of Belonging at an International School, the first book on structural racism in international schools. Available now in hardback and eBook. Portions of this article first appeared in Growing Up in Transit and have been edited for clarity. Pseudonyms are used for research participants who appear in this article.

This article was originally published in The International Educator (TIE Online) on 14 October 2020. It has been edited for clarity.

Further learning

Language & Power: Stories from Asia – Third Culture Kids of Asia discuss how language fluency intersects with social hierarchies in shaping their childhoods and view of the world. Listen on Third Culture Stories, a podcast by TCKs of Asia.

A Foreigner in My Own Family: The Hidden Loss of Language & Intimacy – When a child’s strongest language is different from that of their family, it can create a sense of cultural disconnection that affects the parent-child relationship, even into adulthood. An online forum hosted by TCKs of Asia on October 6, 2020.